(1788-1874)

Father of Fasting and the Hygiene Movement.

American physician and writer who pioneered orthopathy (natural hygiene).

Health care based on physiology, or natural hygiene (as it was later known), began with Isaac Jennings, M.D., in 1822.

“None who believe in the existence of a Supreme Creator and are in the habit of observing the exact order and harmony that prevail in all the material substances and bodies around them will question that their own bodies, which are so “fearfully and wonderfully made,” are constituted in accordance with fixed principles and that ordinarily, at least, all the vital machinery of their physical systems is controlled by expressed law.”

“Obedience to physical law will render obedience to moral law comparatively easy.”

Excerpt From Fasting Supervision and Lifestyle Care (Burton, Burton and Krackler)

About Isaac Jennings

Isaac Jennings (1788-1874) was born in Fairfield, Connecticut, on November 7, 1788, and worked on his father’s farm during his youth. He married Maria, daughter of Deacon Nathan Beers, on Sept. 17, 1805, and had three sons and two daughters.

Educated at Yale, Isaac studied under Eli Ives, MD, from 1809 to 1811. Dr. Ives taught conventional medical practices of the day and focused on the healing “art of drugopathy” (using medications to make sick people well by administering the same medicines that make healthy people sick).

Graduating in 1812, he was licensed to practice medicine. He began his practice in Trumbull, CT, then moved to Derby, CT, in 1820. He received his M.D. from the Yale School of Medicine in 1828. What is truly remarkable about Isaac Jennings is that he quickly realized that in the medical practice he was trained, he wasn’t seeing recovery or progress in his patients.

His loss of faith in drugs occurred while he was attending a young woman afflicted with typhus fever. When it appeared that she might die, he discontinued the use of medication. From a pure spring, he obtained some water, which he placed in a vile and gave to his patient in place of drugs. In a short time, she began to improve and, shortly afterward, completely recovered. This case convinced Dr. Jennings that drugs were worthless, and from then on, he ceased to use them.

Dr. Jennings changed his approach to treating patients in a way unknown to his clients at the time, which laid the groundwork for the beginning of health care based on physiology, or Natural Hygiene.

Instead of using traditional medicine, he carried bread pills, powders made of flour with different scents and colors, and vials filled with pure water. As his patients expected “medicine,” Jennings would give out boxes of bread pills and colored water with specific instructions on when and how to take them while, in reality, providing valuable advice on hydration, diet, and hygiene. With these unconventional “remedies,” he gained an excellent reputation as a “healer.”

Jennings eventually grew tired of deceiving his patients with placebos. He went public with his approach, which later became known as “Hygiene,” the science of health. Despite his revelation, some patients continued with him, while others did not. He faced accusations of fraud and lost the trust of many. However, some open-minded individuals supported him, saying, “If you can heal our illnesses without medicine, then you are the doctor for us.” Instead of receiving praise for his groundbreaking research and innovative approach, his medical peers openly criticized and ridiculed him, ultimately dismissing him as a quack, despite his tremendous success in treating patients.

In 1839, Dr. Jennings moved to Oberlin, Ohio. The town was designed as a health-promoting model colony and later developed into the Seventh-day Adventist Church. He became a member of the Board of Trustees of Oberlin College and served as the city mayor.

Jennings’ work greatly influenced such professional men as Drs. Russell Thacker Trall, James Jackson, and successors in natural hygiene such as Robert Walter, Charles Page, and Felix Oswald. Unfortunately, Dr. Jennings was not a crusader; his lack of crusading spirit proved a significant drawback in the early days of the Hygienic Movement. If he had been more vocal about his views and practices, many early Hygienists’ mistakes could have been avoided.

Dr. Jennings died of pneumonia in Oberlin, Ohio, on March 13, 1874.

Life in the 1800s

(Excerpt from the Natural Hygiene Handbook)

It was in an era of “hog, hominy, and homespun.” Grains, bread, pork, and lard pies predominated in the people’s diet—vegetables and fruits were neglected and considered contraband.

Nobody took baths; a strong body odor was considered a badge of merit. Fresh air was feared. Cold air, damp air, night air, and draughts were especially feared. Houses were unventilated and foul; no sunlight was permitted to enter lest it fade the rugs, carpets, and upholstering.

Sanitation was neglected; tobacco was chewed, smoked, and snuffed almost universally; alcohol was the favorite beverage, and disease was common.

The people suffered from typhus and typhoid fevers, malaria, cholera, yellow fever, diarrhea, dysentery, diphtheria, scrofula, meningitis, tuberculosis, and pneumonia. The general death rate was high, but the death rate among infants and children was appalling; many mothers died in childbirth of child-bed fever.

If you got sick in the early 1800s, you were a candidate for such barbaric “care” as bleeding (drawing blood from you), applying leeches directly on your skin, blistering, burning, and cauterizing (to “draw” the pain away); forced purging and vomiting; and, of course, taking highly-toxic (and long since abandoned) drugs. Water was routinely withheld from the sick, heightening your chances of dying from dehydration. The death rate was relatively high, and the illness recovery rate was quite low. The ‘cures’ were worse than the diseases!

During this time, a popular protest against the bleeding and heroic drug dosing practiced by the “regular” medical profession began. Homeopathy and physio-medicalism arose in response to the demand for milder medication, while the Hygienic System came into being and created opposition to all medication whatsoever.

Impact of Diet and Lifestyle

Jennings did not support the use of alcohol or drugs. He became a congregationalist deacon and was an activist in the temperance movement. He was vegetarian and did not consume coffee, tea, meat, or spices or use tobacco products.

Jenning’s non-use of medicine was based on the idea that nature can keep the human body healthy and that disease results from an imbalance of vital forces, otherwise known as vitalism. In this theory, disease is a unit, and any medication cannot aid its various forms (fever, inflammation, coughs, etc.). He relied solely upon the body’s healing powers supported through rest, fasting, diet, pure air, and other hygienic factors. Diseases vanished before him with a promptness relatively unknown at the time. His fame spread far and wide.

He also noticed that older, experienced doctors, as a general rule, prescribed much less medicine and trusted more to nature. Younger doctors, he observed, tended to trust drugs. Based on his observations, this led him to doubt the prevalent medical practices of the day and, within a very short time, to discard them altogether.

However, before moving from Derby, CT., to Oberlin, Ohio, Dr. Jennings disclosed the secret of his remarkable success (using placebos) and became an adversary of all drug medication. The effect of his disclosure on the community in which he practiced was quite varied. Some denounced him as an imposter, while others continued and followed his protocols with excellent results. The Buffalo Medical and Surgical Journal described Jennings’ methods of utilizing bread pills as “downright quackery” and a “disgrace to the medical profession” despite his incredible results.

Teachings

“What is a disease?”

Jennings was educated at Yale School of Medicine, where he was taught the conventional medical practices of the day and began to practice the healing “art of drugopathy” (using medications to make sick people well by administering the same medicines that make healthy people sick). What is truly remarkable about Isaac Jennings is that he quickly realized that in the medical practice he was trained, he wasn’t seeing recovery or progress in his patients.

So Jennings gave them “medication” with detailed instructions on the administration of the “drugs.”

But in reality, his primary focus with the patient was on lifestyle changes.

“What is a disease?” Jennings wrote an article about disease, and it was included in the publication Eternal Health Truths of a Century Ago. It was, and still is, the question of the day.

Dr. Isaac Jennings – 1820

Jennings simply believed that disease is the abatement of health–nothing more, nothing less. With good health, the organs perform their parts, untiring with undeviating steadiness, as the planets move in their orbits. The first step on the descending scale of health is the reduction of power; second, functional derangement; third, structural derangement, or organic disease.

As the force abates, action, enfeebles, and vacillates, the composition or decomposing functions of organs begin to fail to a greater or lesser degree.

No artificial or unnatural means can make anyone feel better than he or she is in the constant habit of feeling. People of sound constitution and figure of health who live on a simple healthy diet never perceive any good effect from the use of stimulants (e.g., drugs, alcohol). It is actually the reverse.

Dr. Jennings discusses the foundation of disease, or predisposition, as it was called. This condition has been produced by a long, persistent course of violation of the laws of life. He goes on to discuss that this predisposition or depressed state of the body differs greatly in each individual.

Jennings supported the belief that to have a good state of health and to prevent disease, you only had to supply the essentials of Health to the body.

At the beginning of his journey of lifestyle care, he used placebos made from bread into “pills” as well as colored water. Patients expected a “pill or elixir” to heal the body magically. So he gave them “medication” with detailed instructions on the administration of the “drugs.” But in reality, his primary focus with the patient was on lifestyle changes.

Thus, he began orthopathy, known as the “do-nothing cure.” He prescribed a vegetarian diet, as he had been convinced by Dr. William Alcott of the benefits of a flesh-free diet. He also focused on bathing, rest, pure air, fasting, and other hygienic factors.

from the book by Dr. William Alcott.

Vegetable Diet: As Sanctioned by Medical Men

and By Experience in All Ages.

Jennings’ teachings were based on his observation that there are vital laws of life:

- The Law of Action (Exercise),

- The Law of Repose (sleep, rest),

- The Law of Economy (to conserve the vital energy),

- The Law of Distribution (supplying each part of the body with vital energy),

- The Law of Accommodation (adjustment to poisons, etc.),

- The Law of Stimulation (“sounding the alarm” in danger),

- The Law of Limitation (prevention of the waste of vital energy by Nature),

- The Law of Equilibrium (revitalization of weak spots)

Unlike the medical doctors of his time, Jennings felt that nature could “restore her damaged machinery and revitalize it.” He believed disease was a reaction to unfavorable environmental factors. He believed that sickness and eventual death resulted when the laws were broken.

In response to disease, so long as there is no need for nourishment, a cup of cool water and rest is all that is needed. In his writing, Jennings says: “So long as persons are confined to their beds without appetite, there is very little help for them by feeding. It is useless to urge food upon the stomach when there is no digestive power to work it up. Suppose nutrient substances lie a few hours in the warm bath of the stomach without being sufficiently vitalized to protect them from the action of chemical affinity. In that case, they will be converted into acrimonious fluids and gasses and be sources of mischief.”

“The great object to be steadily aimed at in all cases of sickness is to favor the renovating process, which is in constant progression within. Let there be no unnecessary expenditure of vital funds, either through mental exercise or any undue exercise of bodily functions. When there is a disposition to sleep, let it be indulged.”

Dr. Isaac Jennings

Notable Achievements

In his theory, disease is a unit and, in its various forms (fever, inflammation, coughs, etc.), is entirely faithful to the laws of life. Any medication cannot aid these; it relies solely upon the body’s healing powers and placing his patients in the best possible condition to operate the body’s healing processes. Healing is completed through rest, fasting, diet, pure air, and other Hygienic factors, thus allowing his patients to get well.

The beginning of health care based on physiology, or natural hygiene as it was later known, started with Isaac Jennings, M.D., in 1822. At this time, he discontinued his practice of utilizing any drugs.

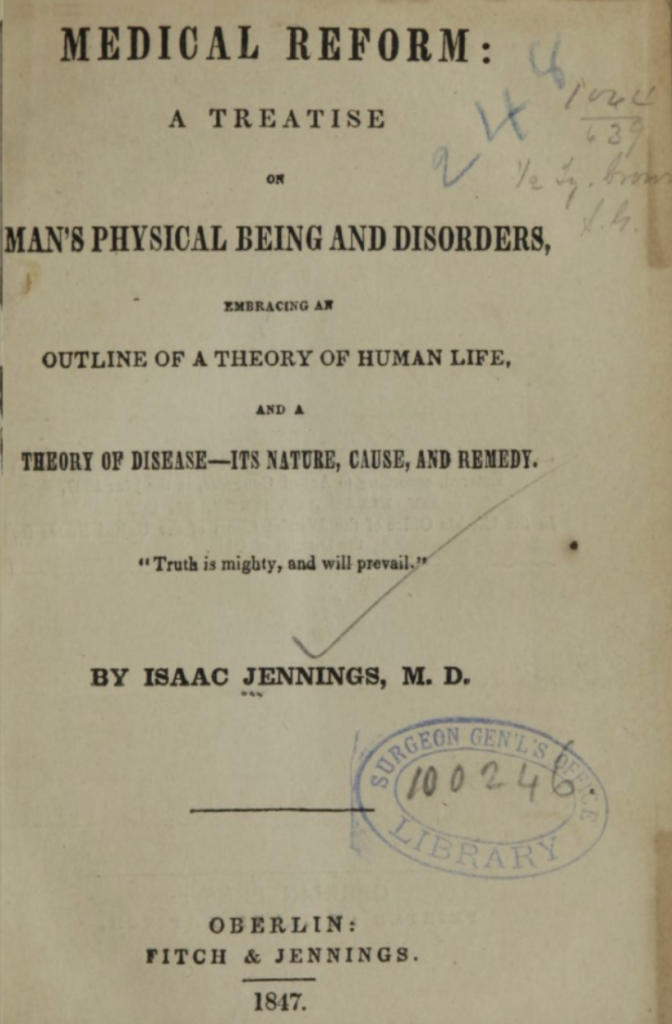

1847

Jennings wrote the Medical Reform: A Treatise on Man’s Physical Being and Disorders. This book opens with the quote: “Truth is mighty and will prevail.” A sentiment truly supported well over 150 years later.

This book dives into his teachings, which were based on his observations that there are vital laws of life: The Law of Action (Exercise), The Law of Repose (sleep, rest), The Law of Economy (to conserve the vital energy), The Law of Distribution (supplying each part of the body with vital energy), The Law of Accommodation (adjustment to poisons, etc.), The Law of Stimulation (“sounding the alarm” in danger), The Law of Limitation (prevention of the waste of vital energy by Nature), and The Law of Equilibrium (revitalization of weak spots).

Unlike the medical doctors of his time, Jennings felt that “impaired health or disease is simply a lower degree of the action of parts affected, that is performed by the same components in their highest state of health, together with such defects in the solids and fluids as flow from such depressed action. In the book, he expands on what disease is, dives into examples, and ends with practical advice on managing disease and restorative movements.

1852

The Philosophy of Human Life, written by Jennings, covers physiology, general pathology, and special reasons for rejecting heteropathy (mode of treating diseases using a wrong or subversive action) and adopting orthopathy (treatment of illness without drugs). The groundwork of each method is quite opposite to the other.

This book is unique because many medical cases were discussed (covering scarlet fever, cholera, typhus fever, whooping cough, croup, consumption, etc.) and shares how patients healed without using drugs well over 150 years ago!

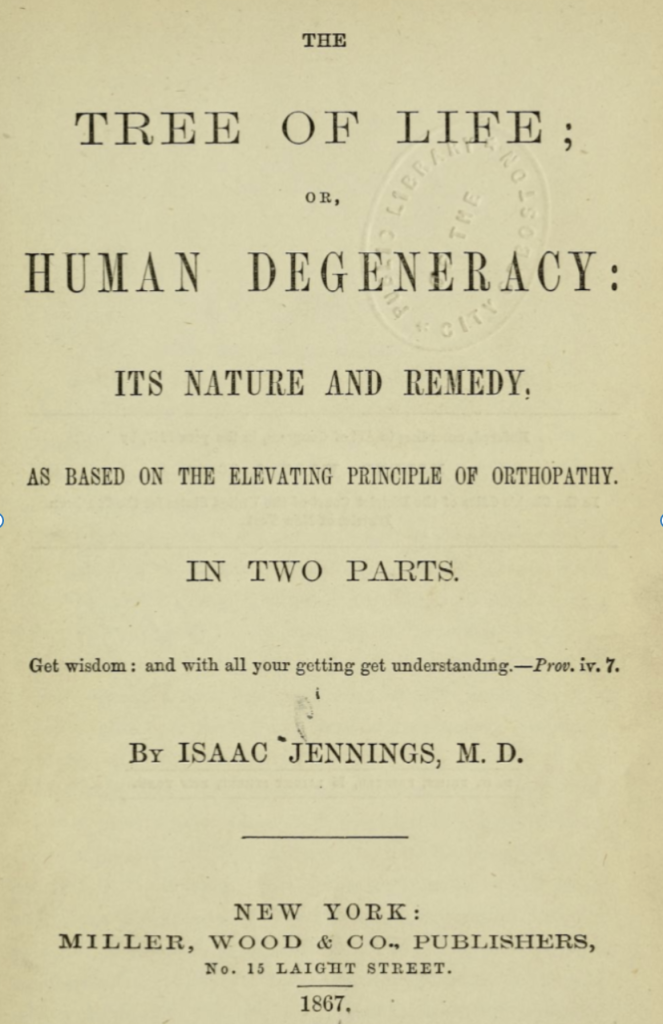

1867

The Tree of Life or Human Degeneracy, its Nature and Remedy, Based on the Elevating Principle of Orthopathy, discusses the nature of human spiritual and physical degeneration. In part one, Jennings focuses on how physical depravity is an accessory to spiritual degeneracy and provides the remedy for man’s spiritual needs.

In part two, he focused on the organic Laws of Life (as listed above under teaching). He delved into the causes of human degeneration, including poor diet, lack of exercise, and environmental toxins. Jennings discusses remedies based on the principle of orthopathy and how the human body can heal through proper nutrition, exercise, and other hygienic factors. Jennings gives practical advice on how to improve one’s health and well-being through the adoption of a healthy lifestyle as well as treatment protocols for croup, dysentery, cholera, etc. His main objective was to evolve his Osteopathic principles and outline general rules of practice.

Jennings was held in high esteem by his contemporaries in many areas besides hygienists. Alcott, Jackson, Troll, and Oswald recognized him as a great medical philosopher. He was a profound thinker who had worked his way out of the Wilderness of Medicine. He became a Shining Light in health reform.

Learn more from: (Read Direct Excerpts)

- Graham, S., Trall. R., Shelton, H. (2009). The Greatest Health Discovery. Youngstown, OH. National Health Association.

- Shelton, H. (1968). Natural Hygiene: The Pristine Way of Life Youngstown, OH. National Health Association.

Our Mission

The mission of the National Health Association is to educate and empower individuals to understand that health results from healthy living. We recognize the integration of all aspects of health: personal, environmental, and social.

We communicate the benefits of a plant-based diet, exercise and rest, a healthy environment, psychological well-being, and, when indicated, fasting.

SUBSCRIBE TODAY AND NEVER MISS AN UPDATE

SUBSCRIBE TODAY AND NEVER MISS AN UPDATE