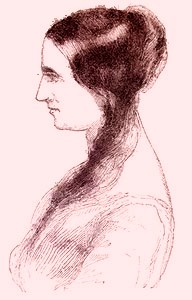

(1810-1884)

About

She devoted her life to educating

women on health and wellness.

Mary Neal was born to Rebecca and William Neal on August 10, 1810, in Goffstown, New Hampshire. In 1822, the family moved to Craftsbury, Vermont. Mary’s education was sporadic in the various small-town schools where she lived. She was a voracious reader and writer who, in her teens, wrote stories and essays for newspapers and magazines. Mary later credited her free-thinking father for her own intellectual assertiveness and independence. William Neal encouraged his daughter to pursue the skills of critical thinking, writing, and debate.

At that time, girls’ education was minimal, so Mary began pursuing her own education. She read and studied what books she could get her hands on. Her brother also studied medicine, and Mary absorbed his books, including works on physiology.

When she was about fifteen, she studied Quakerism. The doctrines appealed to her, and she converted at once. On a visit to her uncle’s farm, she met Hiram Gove. He was a friend of her uncle’s, a Quaker, and was looking to settle down. She was persuaded to marry him, and on March 5, 1831, she became Mrs. Hiram Gove and moved to Weare, NH. Their marriage was a disaster from the start. Her husband had very set ideas about the role of a wife and thought her interest in health indecent.

Married women in the 1800s usually stayed home and performed domestic duties. A woman was seen as her husband’s property and had no power to vote or own land. The wife conceded to the wishes of her husband and operated as a vessel for procreation. Regarding legal rights, it ultimately favored the husband and often absolved him of his abuses towards his wife.

Hiram’s business was unsuccessful in Weare, so the couple moved to Lynn, Massachusetts. Mary opened a girls’ school, began teaching, and started her career in health reform. She was invited to give lectures on anatomy and physiology. Even though Mary was the primary breadwinner, Hiram disapproved of her work and was abusive toward her. Tensions grew between the couple. At this point, Mary considered divorce. For a woman in the 1830s, divorce went against the morals of the day.

In her publications, Mary consistently referred to herself as imprisoned by an abusive marriage to Hiram. She longed for freedom and safety. Mary began to sense that matrimony was detrimental to a woman’s well-being.

Mary, however, was not your average woman. By 1841, Mary had had enough, and she left her abusive husband and returned to her parent’s home. While there, Mary published her first book, Lectures to Ladies (1842), based on her teachings. With her father’s help, she was able to achieve a separation and, a few years later, was able to divorce. Once divorced, she began engaging in love affairs that affirmed her need for passion and partnership.

Mary believed that a marriage without love and equality had a very negative impact on the health of even the strongest of women. Freed from this abusive marriage, both sexually and emotionally, she made it her life’s work to educate women and teach them about their bodies.

When Hiram and Mary divorced in 1847, the response towards her was immediate. Those who previously supported her no longer did. She was unable to have her work published. Divorce was uncommon then, and she was frowned upon in society. She would feel the backlash for the rest of her life.

Mary moved to New York to write for the newly founded Water-Cure Journal and Herald of Reforms. After settling in the city, she created a Graham Boarding House and taught women about physiology, health, and illness treatment.

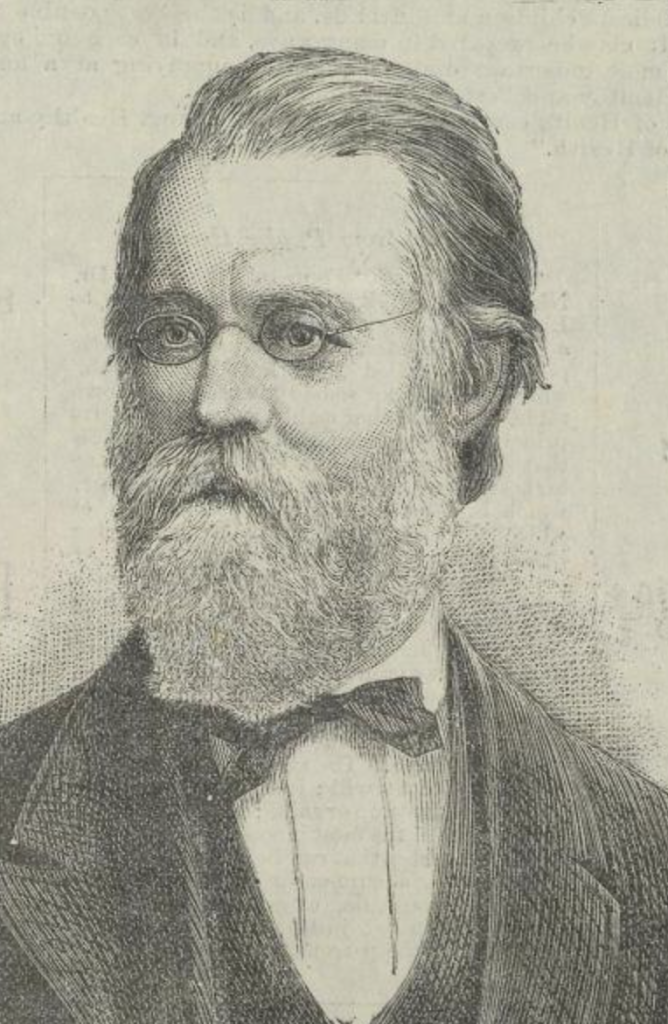

He completed his medical studies to

practice and work alongside his wife.

In 1832, Sylvester Graham lectured in Boston on his crusade for health reform. Thomas Low Nichols, a medical student at Dartmouth, attended that lecture. Little did Thomas realize the impact that meeting would have on his life. He quickly gave up his medical studies and became a journalist. Thomas wrote for and became the editor of the New York Evening Herald and was politically active in several movements, including Women’s Rights. It was through these avenues that he met Mary Gove.

Graham also stopped in Lynn, Massachusetts, where Mary attended his lecture. After Thomas and Mary heard his speech, they converted to a Graham Lifestyle. It made sense to both of them. They connected, supported this lifestyle together, and eventually married.

Dr. Thomas Nichols began the Water-Cure Journal and Herald of Reforms, Devoted to Physiology, Hydropathy, and the Laws of Life in 1845. He edited the publication, and they both wrote. It was their first significant project. These journals were devoted to physiology, hydropathy, and the Laws of Life. It included articles about the water cure, hygiene, dietetics, and dress reform. The journal continued on after 1855 as the Hygienic Teacher and Water-Cure Journal.

Mary continued to write under the pen name M. Orne, publishing several books. Under her name, she published Lectures to Women on Anatomy and Physiology with an Appendix on the Water Cure in 1846. This book is a culmination of her many lectures. She begins with the importance of studying anatomy and physiology, dives into the human body’s various systems, and includes chapters on nutrition and education.

Strong opposition existed to women entering the medical profession at the time. Women were not permitted to attend medical colleges, and no other schools of “healing” were open to Mary. She was, therefore, at a significant disadvantage. Thomas decided to complete his medical studies and get a license to practice and work alongside his wife. He studied at the University of New York under Valentine Mott and graduated with high honors in 1850.

In 1851, Mary and Thomas Nichols opened the American Hydropathic Institute. It was the first medical establishment created to teach the principles of water therapy. Dr. Nichols taught chemistry, anatomy, physiology, pathology, medicine, and surgery. Mary taught women’s physiology and the diseases of women and children. What is unique here is that men and women were equally accepted at the American Hydropathic Institute.

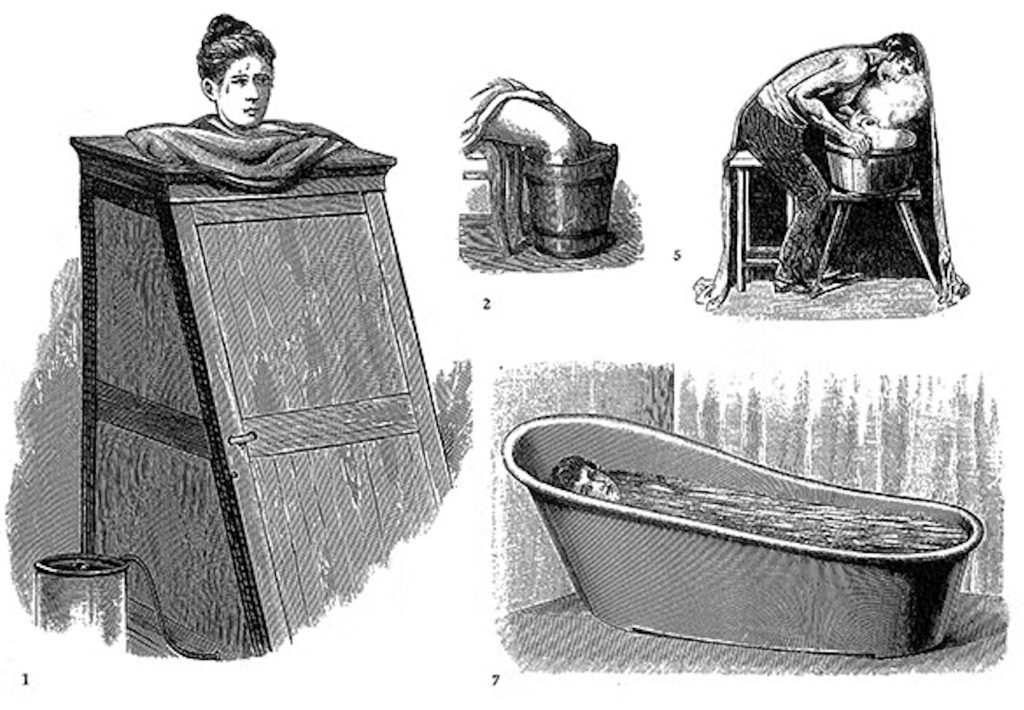

Hydropathy in the 1800s supported the idea that if water invaded any cracks, wounds, or imperfections in the skin, it would flush out impure fluids. Hydropathic techniques used included damp bandages, sweating, the plunging bath, the half bath, the head bath, and the sitting bath.

A large part of the lifestyle was also based on living simply. These lifestyle adjustments included dietary changes, fresh air, sleep, and drinking large quantities of water.

Next was their publication in 1853, Nichols’ Journal of Health, Water-Cure and Human Progress. It was devoted to individual and social health, education, hydrotherapy, women’s rights, and happiness.

Mary and Thomas moved to Yellow Springs, Ohio, in 1856, where they established another water cure institute. Their institute became both groundbreaking and scandalous at the time. Housing was provided for men and women. Studies included the health benefits of a vegetarian diet, the healing properties of hydropathy, and the importance of maintaining a disciplined life.

These positive attributes became clouded by Nichols’ belief in free love and the restraints of traditional marriage. Folks who felt strangled by the constructs of society were drawn to the institute and participated in free love practices. Thomas gave local lectures such as “Free Love: a Doctrine of Spiritualism.” These lectures were scandalous and deeply frowned upon by the local community. The public was not ready for this. Their advocacy of free love also alienated them from other reformers. Where they were once beloved reformers, these taboo ideas caused many followers to condemn these new beliefs. Their views were too abhorrent to merit a continued following.

When the Civil War erupted, Mary and Thomas boarded a ship and sailed for London. They detested war and would not support either side. Shortly after their arrival, they began writing for British journals. When the opportunity presented itself, they lectured on vegetarianism and the laws of health.

In 1867, they moved to Malvern, England, the site of James Gully’s hydropathy spa. Here, they began a water cure treatment facility. During this time, Mary continued to write and published A Woman’s Work in Water Cure and Sanitary Education.

In 1878, they both returned to writing and continued editing the journal publication Herald of Health until Mary passed on May 30th, 1884.

Life in the 1800s

In colonial America, a woman administered most medical care at home. However, by the 1820s, male doctors had displaced women, even in midwifery. Women were no longer trusted to manage their well-being, and the old ways of sharing knowledge from woman to woman began to wane in popularity, especially in urban areas.

If you died in the process, it was thought that the “bad blood” was not gotten out in time.

Medicine of the 1800s was a gruesome ordeal. Bloodletting, ignorance of germs and infection, the use of mercury pills and laxatives, and “mainstream medicine” were some of the biggest obstacles to good health. Women were not educated about nutrition, health, or their own body. The state of women’s healthcare indeed left much to be desired.

The practice of medicine was a male monopoly. Medical colleges would not admit female students, and practicing physicians rejected all female applicants who wished to serve an apprenticeship in medicine. Examining and licensing boards would not license females. Women were not admitted to study medicine until a woman’s medical college was established.

The establishments started by Mary and Thomas Nichols and Russell Thacker Trall admitted female students and graduated women with the degree of Doctor of Medicine. Moreover, these women doctors were eagerly received and made excellent names for themselves.

However, as the population moved into unsettled areas of the country, particularly in the South and West, a lack of access to physicians contributed to women once again playing a significant role in providing health care. The Popular Health Movement (1830s–1850s) coincides with a resurgence of women as health practitioners.

Teachings on Diet and Lifestyle

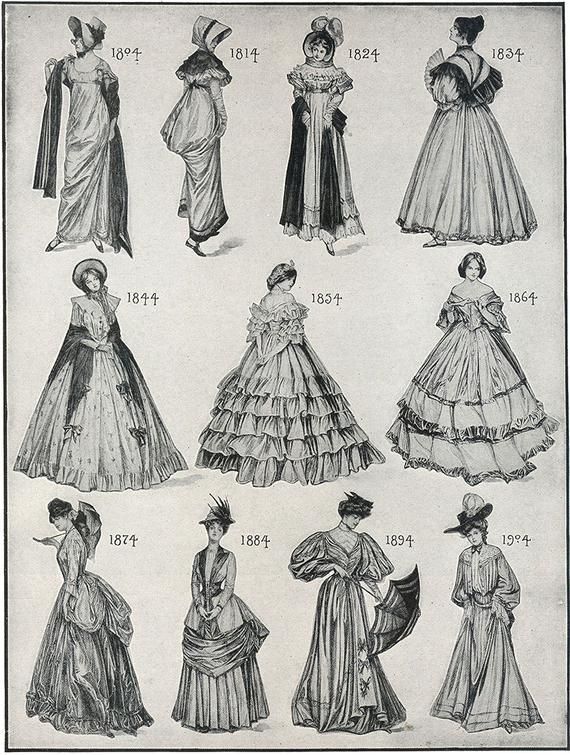

Mary was the first woman to lecture on Grahamism (limiting their diets, strict mealtimes, avoiding meat, spices, and condiments, abstaining from tea, coffee, or alcohol, breathing fresh air, and bathing regularly) and incorporating this into her lectures. She also supported the battle for women’s rights, sexual education, and dress reform. The clothes worn by women of that period were horrific. Stiff whalebone corsets and long dresses inhibited breathing and greatly restricted movement. Even before the Civil War, Mary advocated wearing slacks as a matter of health and equality. (Mary preferred bloomers.)

Mary’s views began to evolve as she became more deeply entrenched in reform. She initially focused on healthcare, and while her fame as an activist flourished, Mary always prioritized women and the democratization of wellness.

She began to formulate that it was not just the realm of medicine that kept women from living their healthiest lives. In some of her publications, Mary consistently referred to herself as imprisoned by her first marriage. Feeling stymied and suffocated, she longed for freedom and safety. The misery of her marriage to Hiram played a significant role in creating her reformist ideals towards marriage. As she documented in her writings, she intensely disliked the institution. She believed matrimony was detrimental to a woman’s well-being. Mary emerged as a radical critic of the standards of marriage that afflicted her generation. She thought that society dealt women an unfair hand and that their health suffered as a result.

Mary’s path to understanding the water cure stemmed from her illnesses. She practiced the water cure on herself and learned some of the founding principles of hydropathy. Additionally, Sylvester Graham’s health principles, which she followed, impacted her lectures, publications, and teaching. She presented health as a skill that everyone could harness. As she established herself as a medical practitioner, she realized that the water cure was a profession in which women could especially thrive. It would allow them to become potent agents for both health and female empowerment. Hydropathy represented a far more welcoming sect of medicine to women than more traditional paths.

Hydropathy in the 1800s believed that if water invaded any cracks, wounds, or imperfections in the skin, it would flush out impure fluids. Hydropathic techniques used included damp bandages, sweating, the plunging bath, the half bath, the head bath, and the sitting bath.

Much of the treatment was also based on living a simple lifestyle. These lifestyle adjustments included dietary changes and, of course, drinking large quantities of water.

Stiff whalebone corsets and long dresses inhibited breathing and greatly restricted movement.

Mary began giving presentations to educate women. Her lectures were preserved in an 1841 publication entitled Lectures to Ladies on Anatomy and Physiology.

how to exercise and eat cleanly.

In 1851, Mary and Thomas Nichols opened the American Hydropathic Institute. It was the first medical establishment created to teach the principles of water therapy. Dr. Nichols taught chemistry, anatomy, physiology, pathology, medicine, and surgery. Mary taught women’s physiology and the diseases of women and children. She was an early advocate of women becoming physicians.

The American Hydropathic Institute provided the foundations for her subsequent publication, Experience in Water Cure, which explained her theories of health, such as diet, fresh air, cleanliness, exercise, and the absence of hurry.

Mary believed that women in the 1850s were imprisoned in many ways. One step towards alleviating that burden was treating and educating women on their physical health. However, during the second half of her career, she and Thomas moved in a very different direction. They wrote on free love and ideas of marital reform. Unfortunately, these free love ideals were too radical for their followers. Their colleagues, friends, and supporters abandoned them, and their fame waned.

Notable Achievements

Mary Gove Nichols was one of the most influential women in America. She was a radical social reformer and a pioneering feminist. She advocated for women on many levels.

After hearing a lecture from Sylvester Graham on his crusade for health, Mary instantly began to follow his lifestyle. Grahamites, as they were called, limited their diets with strict mealtimes, avoided meat, spices, and condiments, abstained from tea, coffee, or alcohol, breathed fresh air, and bathed regularly. She incorporated these ideas throughout her lectures, courses, and publications.

In 1851, Mary and her second husband, Thomas Low Nichols, opened the first American Hydropathic Institute in New York City. Mary’s mission was to make the water cure accessible to all, culminating in a place that would allow both men and women to learn treatments and disseminate that knowledge to the public. Mary taught physiology, midwifery, and the diseases of women and children. Thomas lectured on chemistry, anatomy, physiology, pathology, medicine, and surgery. They aimed to recreate “a complete medical education” by combining “the theory and practice of Water-Cure” and allopathic and homeopathic methods. They believed that combination educated students on the knowledge and merits of each system.

Mary’s crusade for women’s education became integral to her school’s identity. The Hydropathic Institute’s first graduating class boasted nine women and eleven men. Women who graduated from the institute often opened cure centers or worked in private practices to support the use of the water cure. Women were found to be the strongest champions of “woman’s rights” among Hygienists.

In 1852, Mary published Experience in Water-Cure: a Familiar Exposition of the Principles and Results of Water Treatment, with an explanation of the water-cure process, advice on diet and regimen, with a particular focus on the treatment of female diseases, water treatment in childbirth, and the diseases of infancy.

In 1874, Mary summarized what she had learned throughout her career in the book A Woman’s Work in Water Cure and Sanitary Education to continue to help and educate other women.

The arrival of the water cure coincided perfectly with the nationwide frustration with the state of professional healthcare. Hydropathy, marketed as a safer approach to healing, emphasized nature’s power as a cleansing and detoxifying agent. Hydropathists thought of themselves as aids to the natural course of recovery. Additionally, hydropathy appealed to Americans who could not travel for medical care. Publications, such as Joel Shew’s Water-Cure Journal, taught readers ways to treat illness at home, with additional tips on how to exercise and eat cleanly.

Mary emphasized how women would benefit from marriage equality and health reform. She passionately believed that women should assert independence over their health and relationships. She aimed to offer women what they rightfully deserved: a life of health and wellness.

Few living women deserve more respect than Mary Gove Nichols. She devoted her life to educating women on health and wellness. Embarking on an intellectual and professional collaboration with her husband, they challenged the inequities of conventional marriage, demanded every woman’s right to control their body, and advocated universal good health.

Learn more from: (Read direct excerpts)

- Graham, S., Trall. R., Shelton, H. (2009). The Greatest Health Discovery. Youngstown, OH. National Health Association.

- Lennon, J., Taylor, S. (1996). The Natural Hygiene Handbook. National Health Association, Youngstown, OH.

- Shelton, H. (1934). The Science and Fine Art of Natural Hygiene – The Hygeientic System: Volume I. National Health Association, Youngstown, OH.

- Shelton, H. (1968). Natural Hygiene: The Pristine Way of Life. Youngstown, OH. National Health Association.

The NHA wishes to remind the readers that nothing in this or other publications is intended to constitute medical treatment or advice. Readers should be aware that some previous publications do not reflect the NHA’s current teachings or health approaches.

Our Mission

The mission of the National Health Association is to educate and empower individuals to understand that health results from healthy living. We recognize the integration of all aspects of health: personal, environmental, and social.

We communicate the benefits of a plant-based diet, exercise and rest, a healthy environment, psychological well-being, and, when indicated, fasting.

SUBSCRIBE TODAY AND NEVER MISS AN UPDATE

SUBSCRIBE TODAY AND NEVER MISS AN UPDATE