Excerpt From:

Graham, S., Trall. R., Shelton, H. (2009) The Greatest Health Discovery. Youngstown, OH. National Health Association.

“Sylvester Graham

Few people today realize that “graham bread” was so popular at one time, and today’s graham crackers were named after Dr. Sylvester Graham, one of the earliest nineteenth-century health reformers or hygienists. Indeed, even his name is known to relatively few—though his teachings enormously influenced that century.

Graham was born in 1794 and was the youngest of seventeen children. He was a delicate child and, at the age of sixteen, was thought to have “contracted consumption.” Indeed, his naturally frail constitution remained throughout, and—as he points out—it was only his reformed diet and hygienic mode of life that enabled him to stay in active health and alive as long as he did.

Not long after he was born, his father died. Graham’s mother possessed a melancholy and morbidly religious mind, which doubtless exerted an influence on the naturally sensitive child—influencing him, later on, to join the Presbyterian church and become a preacher.

“In a way, however, it was fortunate that he did so, as he became interested through this temperance reform; this, in turn, led to the study of anatomy, physiology, and health generally, culminating in his ultimate emergence as a great health teacher. During this early period, he wrote his little book on “Chastity” and began his interest in moral and social reform.

Graham wrote articles for magazines and a booklet entitled An Apology, which was a reply to those critics who pointed to his frail constitution as a refutation of his teachings. He replied to such criticisms that living his health teachings was the only thing that kept him alive.

In 1823, Graham entered Amherst College and proved himself a gifted orator. Seven years later, he was engaged by the Pennsylvania Temperance Society to present their cause. Two years later, he came forward as the champion of Natural Hygiene and living reform. He boldly asserted that right living is a more specific means to health than a resort to physicians and drugs.

Sylvester Graham lectured in New York, Rochester, Providence, Buffalo, and many other cities. When we consider that over one hundred years ago, when the city of Rochester was but a small place and people had to travel by buggy or on foot, he attracted an audience of three thousand people in that city, some ideas may be gained from the popularity of the man and his message. He soon had a significant following.

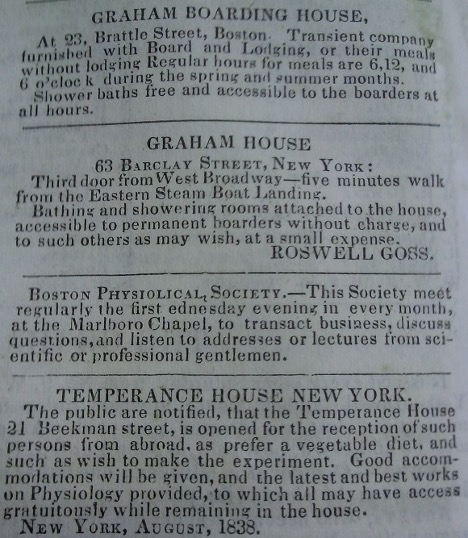

Books and magazines explaining the Graham system were published. Graham boarding houses and Graham restaurants came into existence. In Boston, a Grahamites organization established the world’s first health food store. Organizations were formed in various cities and even in the colleges. At Brook Farm, near Boston, a Graham table was set. The same thing was true at Oberlin College. In Boston, a particular bookstore was established to provide food for thought.

He died at age 58 on September 6, 1851.

Vol. III No. 13. Boston and New York, Saturday, June 22, 1839

The medical historian Richard Harrison Shyrock says: “Graham’s work was scientific in the sense that it included the current physiology as well as hygiene, it always having been his contention that the latter must rest on a rational basis of ‘physiological principles.’ For this reason, he became an ardent advocate of the popular teaching of physiology, and his followers were perhaps the first group to urge its introduction in public schools.

Graham was also the first to advocate the education of the young in sex hygiene.

His great work was The Science of Human Life—an enormous volume of 650 closely-printed pages, published in 1843. The first eight chapters are devoted mainly to anatomy and physiology; the next two deal with man’s mental and moral powers. Chapter eleven considers the question, “How long can man live?” In the twelfth chapter, we come to the general rules of hygiene.

The succeeding eleven chapters are devoted to the question of diet and food reform, and in these, Graham elaborates his arguments in favor of vegetarianism and even a fruitarian diet. He was, in fact, one of the first to show the scientific basis on which a frugivorous diet rests.

The subjects discussed in the remaining chapters cover such topics as regularity in eating, thorough mastication, hygienic cookery (with attacks on salt, condiments, and spices, tea, coffee, alcohol, etc.), the physiology of hunger, the quantity of food necessary to sustain life, the dangers of excess, fasting, sleep, air, bathing, exercise, and a series of attacks on drugs and orthodox medication.

Graham was emphatic in his contention that so-called “epidemic diseases” could invariably be avoided by those who adopted the reformed diet and way of life.

Modern dietary science (trophology) may have had its beginnings with Sylvester Graham, for until his time, there was a great deal of ignorance regarding a healthful diet.

It will be evident from the above general summary that Graham’s book covered practically the entire field of hygienic reform and, considering that it was written more than one hundred years ago, constitutes a remarkable document and a veritable classic on the subject.

The early European settlers had brought the idea that fruits and vegetables, especially uncooked, should be avoided. The New York Mirror warned on August 28, 1850, that fresh fruits should be religiously forbidden to all classes, especially children. Two years later, the same paper stated all fruit is dangerous, and because of the cholera epidemic, city councils prohibited their sale wherever they had jurisdiction. “Salads were to be particularly feared.” Robley Dunglison, the famous physiologist of the period, appears also to have shared this view.

In August 1832, the Board of Health at Washington, D.C. prohibited, for ninety days, the importation into the city of cabbage, green corn, cucumbers, peas, beans, parsnips, carrots, eggplant, squashes, pumpkins, turnips, watermelons, cantaloupes, muskmelons, apples, pears, peaches, plums, cherries, apricots, pineapples, oranges, lemons, limes, coconuts.

While not prohibited for sale, potatoes, beets, tomatoes, and onions were advised to be eaten in moderation by the Board, who said the prohibited articles “are, in their opinion, highly prejudicial to health at the present season.” About all they left for the people of Washington to eat were beef, bacon, and bread, with beer and wine.

In 1832, Dr. Martyn Paine of the New York University Medical School argued that garden vegetables and almost every variety of fruit had been known to develop the deadly cholera. He believed people should restrict themselves to lean meat, potatoes, milk, tea, and coffee to avoid it. That same year in New York City, Graham attacked the false beliefs concerning fruits and vegetables and endeavored to induce Americans to eat more and cease consuming animal foods.

Graham not only challenged the view that fruits and vegetables cause cholera and that plenty of meat and wine will prevent it, but he declared that a diet of fruits and vegetables with entire abstinence from all alcoholics, tobacco, condiments, etc. and from all animal foods, was the best prevention of cholera.

It is interesting to note, in this connection, that Graham’s first observations of the effects of diet on health were made in Philadelphia and related to the part a vegetable diet played in preventing cholera. A small sect of Bible Christians had migrated from England to Philadelphia. They abstained from all animal foods (flesh, eggs, milk, cheese, etc.), condiments, and stimulants. They used no tea, coffee, alcohol, or tobacco. It was their view that flesh-eating violated the first command given by God to man—that he should eat the fruit of the trees of the Garden.

Ten years before Graham lectured in Philadelphia for the Pennsylvania Temperance Society, the city had experienced a severe epidemic of cholera. The death rate was high. Contrary to what was expected from the medical teachings of the time, not a single member of the Bible Christian Church had cholera. This fact made a deep and lasting impression on Graham and caused him to turn his attention to the study of diet.

No longer was Graham a mere temperance lecturer. His first series of lectures given the following year in New York City were on the causes and prevention of cholera. So radical and revolutionary did his speeches seem to the medical profession and most of the educated people of the time that it required nearly another quarter of a century for them to discard their false notions about vegetables and fruits causing cholera and concede that Graham may have been right.

Many who heard Graham’s lectures followed his advice, and thereupon, the physicians, butchers, and others of New York reported that the Grahamites were dying like flies of cholera. Graham returned to New York and, being unable to find a single instance of death from cholera among those who had adopted the plan of eating and living he offered, challenged his maligners, through the public press of the city, to bring forth a single case of death among his followers. They did not and could not do this, but they did not cease to circulate the lies.

Graham pointed out that “in America, where animal food is almost universally consumed in excess, and where children are trained in it even before they are weaned, scrofulous affections were exceedingly common, and lead to that fearful prevalence of pulmonary consumption, which has rendered that complaint emphatically the American Disease.

In addition to this, Graham pointed to “well-fed vegetable-eating children of other countries in all periods of time” and to examples of “feeble and cachectic children, and even those who are born with a scrofulous diathesis” who had been “brought into vigorous health on a well-ordered vegetable diet, under a correct general regimen” as proof that the “very best health can be preserved in childhood without the use of fleshment.

Even the unexpected happened. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, a conservative and established periodical, endorsed Graham’s cause in its October 21, 1835 issue. It declared that his introductory lecture in Boston would have reflected honor upon the first medical men in America.

The fear of the garden and orchard produce lingered for many years after Graham’s work began. Indeed, many stories in the early 20th century show how watermelons, cantaloupes, cucumbers, and a few other fruits and vegetables were responsible for malaria.

During the cholera year of 1849, the Chicago Journal strongly condemned the city council of that city for not prohibiting the sale of fruits and vegetables as had been done in other cities since, as the Journal said, the “sad effects” of using such foods were “so apparent.” In 1867, it was reported by the press that someone, by merely passing a fruit stand laden with spoiled peaches, had suffered an “attack” of the gripes.

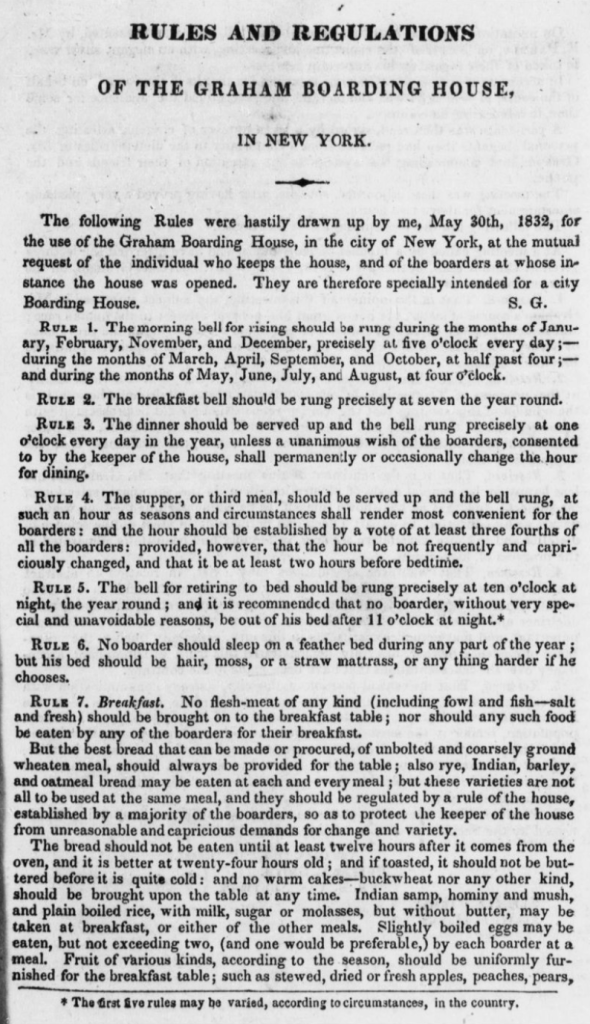

Graham House Rules and Regulations From the book

- Graham, S. (1833). A Lecture on Epidemic Diseases Generally, and Particularly the Spasmodic Cholera. New York, Mahlon Day.

Excerpts from:

Shelton, H. (1968). Natural Hygiene: The Pristine Way of Life Youngstown, OH. National Health Association.

“It was into the milieu of doubt and uncertainty, of disease and death, that Sylvester Graham threw a stone in 1830. A rock hewn out of physiological truth could not help destroy many fallacies and provide a way of escape for the thinking and observing members of society. A revolution was started that will not cease until the old order has been completely demolished and a new one fully established. Only the existence of a revolutionary situation, created by the failures and contradictions of medical theories and practices, made possible the immediate and widespread acceptance of the truths announced by Graham, his contemporaries, and successors.

Graham’s lectures and writings represent launching a crusade for health and what he called “physiological reform” of the people, not the beginning of Hygienic practice.

“An editorial in the Herald of Health, January 1865, says of Sylvester Graham that he was “pre-eminently the father of the philosophy of physiology. In his masterly and celebrated work, the ‘Science of Life,’ he has given the world more philosophy and more truth concerning the primary and fundamental laws that relate man to external objects and other beings than any other author ever did–than all other authors ever have. Though his writings are in poor repute with the medical profession, and his vegetarian doctrines are condemned by the great majority of medical men of the present day, no one has ever undertaken to refute his arguments and probably never will. To him, as to all other pioneers in Health Reform, the customary remark applies: he was a diligent worker and thinker. His book has now been before the people of this country for about thirty years, republished and circulated extensively in Europe, and is regarded everywhere as the pioneer work in the great field of physiology and hygiene.

“For a few years preceding his death, which occurred in 1851, he had been engaged in writing a ‘Philosophy of History,’ to which he had devoted much time and close and careful study, one volume of which has been published since. He died at the age of fifty-seven. Undoubtedly, he would have lived many years longer if he had labored more moderately. It should be stated, however, that he inherited a frail constitution. Before he grew to manhood, he was regarded as in decline. He was saved from fatal consumption only by a resort to those agencies and conditions which are now understood by the phrase, ‘Hygienic Medication.’ ”

Hygienic Medication at the time this editorial was penned included the use of modalities of the “Water Cure,” whereas Graham’s recovery occurred before Priessnitz had originated his water cure. The importance attached to Graham’s work is further attested by a statement in this same editorial that his lectures and writings had prepared the public mind to investigate a new mode of treatment. ”

“Also, there is the statement made by Robert Walter, M.D., in an article in the January 1874 issue of The Science of Health, that “Sylvester Graham, with ‘The Science of Human Life,’ made a great step in advance; and, though some of his theories are not what later developments would approve, he nevertheless made a valuable attempt at systematization.”

Excerpts from:

Graham, S. (1837). Lectures On the Science of Human Life. New York. Fowler and Wells.

Sylvester Graham was descended from a family of some distinction. Sylvester Graham was the 17th child. He was born in 1794, the son of his father’s old age, who died soon after. His mother was so overwhelmed with grief and care that she was the subject of a melancholy derangement. Under these circumstances, the Youth of Sylvester Graham was much neglected.

Sylvester Graham was left to the care of an uncle and was thought to be dying. He recovered, however, and one of his brothers acted like a father to him and placed him under the charge and guardianship of his brother-in-law, a farmer. He lived with this person for some years. He did all the drudgery of the farm, being treated like a laborer, and having many hardships and bufferings to undergo, feeling all the time ambitious and restless, for, as he says, “I had heard of the noble deeds, and longed to follow to the field of fame.” Though without cultivation, he was naturally clever and asserted and maintained a superiority among his Playmates, and in whatever Society he was thrown into, his powers of description, imagination, and active and stirring spirit always made him a center of attraction.

At 14, he was residing with his mother at the family mansion. Though he had more opportunities to learn and quickly made himself master of that which he applied himself, he was still untutored and occupied his time in all social amusements.

In 1810, he went to New York and was a clerk to a merchant for a few months; This was his 16th year. Consumption symptoms appeared then, and Sylvester was sent into the country.

In his 19th year, he began educating his mind earnestly and entered into studies under a judicious tutor. After four months’ tuition, his master recommended that he become a teacher. In this capacity, Sylvester exhibited all the fire and energy of a reformer, and such was the influence that he gained over his pupils that he produced an impression on their minds and carried them on in the career of improvement so rapidly as to get his name extolled in the neighborhood. Here again, illness seized him, and he was obliged to give up his school.

A religious feeling penetrated his heart when overcome with physical weakness and melancholy forebodings, and he joined in prayer meetings, where he eloquently poured forth his sentiments and greatly affected his audience.

Sylvester went to Albany with his sister, but he was weak, emaciated, and miserable. With the hope of benefiting his health, he went by steamer to New Brunswick, New Jersey. On this journey, Graham made several valuable acquaintances and friends.

In 1823, he resolved to study at Amherst College to qualify himself for the ministry. His studies were not pursued very closely, as his health could have been better, and he suffered from nervous headaches.

(Miss Earls), One of whom he very soon afterward married and had no reason to repent the match. After his marriage, he became a preacher in the Presbyterian Church. He was popular as a preacher and soon took up the temperance cause while studying anatomy and physiology. He continued lecturing with great success and was always well-received and very impressive.

Sylvester Graham lived the latter part of his life in Northampton, Massachusetts. He had four children. In 1849, his health was such that he could not survive long. In those times, physicians trusted, even more generally than now, stimulants, and Graham occasionally submitted to a treatment that was contrary to his judgment. He was, however, worn out; his mind had always been too active for his feeble frame, and on the 6th day of September 1851, in his 58th year, his Spirit escaped from its mortal tenement, where it had been so long struggling to work out the happiness of the human race.

The followers of his system of diet were for some time called Grahamites, and there were Graham hotels and Graham bread. The distinguishing character of his system was maintaining the advantage of a well-selected diet from vegetable products in preserving health and securing a long life.

Excerpt From

Herbert M. Shelton

Sylvester Graham regarded hunger as a unique sense, like that of taste and smell, founded upon the body’s dietary wants. His thought was that, as nutrition requires a constant supply of alimentary substance from without, this supply requiring the exercise of voluntary powers, it was essential that the center of “animal perception” should be made aware of the nutrient needs of the organism. Accordingly, when the body is healthy, the stomach, which he regarded as the primary organ of external relation regarding food, is brought into a peculiar condition that is felt as hunger. Our position today would be that since food is first taken into the mouth, prepared for swallowing, and where the first steps in preparing the stomach for food reception are made, the sense of hunger would or should be felt there. Indeed, as the nose is also involved in food selection, the sense of hunger may be partly felt in this organ. We now know that hunger is felt in the mouth, throat, nose, and, to some extent, the whole body.

Although hunger, in the healthy individual, always informs us, with accuracy, when food should be taken, Graham said that hunger has no power to determine what food is best. We have to depend upon the senses of taste and smell to discriminate between wholesome and unwholesome substances. Nonetheless, although this is a fact that Graham did not stress, hunger is often accompanied by a distinct desire for a particular kind of food.

The depraved stomach, he held, its integrity impaired by previous abuse, may give rise to sensations that are mistaken for hunger but which are, in reality, demands for irritation or stimulation. He says that this kind of hunger recurs with no regard for the nutrient needs of the organism and is likely to be irregular, erratic, and despotic, according to the habits of the individual, the condition of the stomach, and the nervous system. The imperiousness and intensity of this fictional hunger are not regulated by the urgency of the body’s need for food but wholly by the “intensity of the morbid demand of the stomach for stimulation” so that food will not satisfy it unless the accustomed stimulant accompanies it. Hunger of this kind is no accurate indication of the wants of the organism. It is a mistake to call such symptoms hunger; it was also a mistake to regard them as a demand for stimulation. They were and are conditions of unease and weakness that appear when the stimulant has been expelled. They are not demands for more abuse.

The presence of what is commonly termed appetite does not always indicate that food is needed. It is not necessarily evidence of health. Neither does it suggest that the individual has good digestion and will benefit from eating. Although it is popularly believed, a man is only sometimes well so long as he desires to eat. To prove this, it is only necessary to point to the fact that many chronic sufferers complain of being ravenous—” I am hungry all the time,” they often complain. They eat continually, even rising at night to eat additional food.

“This alleged demand for food is more properly termed a “perverted appetite.” That it is temporarily relieved by food does not prove it was an expression of a genuine physiological demand for food. A cup of coffee relieves the headache of the coffee addict, a shot of morphine temporarily relieves the suffering of the morphine addict, and a cigarette temporarily relieves the jitteriness of the tobacco addict. Still, such relief does not prove that there is any physiological need for these poisons. The food addict is in the same boat as the drug addict and suffers similar “withdrawal symptoms” when he does not receive his accustomed meal.

Much of this supposed demand for food is a craving for coffee, salt, pepper, or other irritants and poison to which the stomach has become accustomed. Much of it is simply irritation of the digestive tract resulting from overeating, wrong eating, and the eating of stimulating foods. A toxic state of the digestive tract resulting from indigestion, can set up symptoms galore that are mistaken for hunger. True hunger never manifests in the stomach, and it is always in the nose, mouth, and throat. It is common to mistake distress in the stomach region for hunger.

“Chapter 33 A WAY OF LIFE

In his analysis of the work of physicians, in the introduction to his Aesclepian Tablets (1834), Sylvester Graham characterized the great mass of physicians of his day as “a mere drugging craft.” Elsewhere, he referred to it as “the deadly virtues of the healing art.” The actual work of the physician, he said, was not merely to observe symptoms with reference to the drugs to be prescribed but to “teach mankind the laws of life,—the nature, and the causes of disease: to guide their fellow-creatures in the way of health; and when diseased, to make them wise by making them acquainted with the causes of their sufferings: to remove those causes, and thus enable the relieved system to recover health,” and, in rare special cases, where he may think his medicine is a “necessary evil,” to administer it as such.

“This was a new role that Mr. Graham prescribed for physicians, one they did not like and did not accept. Physicians had never functioned as teachers and health advisers. They confined their work to symptom-shooting with pills, powders, plasters, potions, pukes, purges, and bloodletting, leaving causes untouched and the ways of life uncorrected. The people called them when ill and ignored them when well, for disease was their stock-in-trade. Graham quotes the “distinguished Hoffman, a physician of great eminence,” advising in his Seven Rules of Health, “Fuge medicos, et medicamentum si vis esse salvus!” “Avoid medicine and physicians if you value your health.” He also quotes “one of the most eminent English physicians of the present day,” whom he does not name, as saying with reference to the modern (early in the 19th century) practice of medicine: “All things considered, it was better for mankind, if not a particle of medicine existed on the face of the earth.

SUBSCRIBE TODAY AND NEVER MISS AN UPDATE

SUBSCRIBE TODAY AND NEVER MISS AN UPDATE