Quote

It is good for the well man to eat, drink, exercise, labor, and partake of all enjoyments. But the best thing for the sick man may be to stop eating entirely and to rest his mind and body. The effort to digest food, exercise, and keep up is a cause for exhaustion. Fasting, or absolute rest to the stomach, is one of the simplest means of cure in both acute and dyspeptic diseases. No food, not one atom, should ever be taken in any acute disease until cured. Fasting with water is all that is needed. And in all chronic diseases complicated with dyspepsia, the digestive system needs absolute rest more than anything else. Let such a patient eat nothing and drink water for three weeks, and it will go further to secure a cure than months in the most active treatment.

Excerpt From The Greatest Health Discovery

Sylvester Graham, Russell T. Trall, and Herbert M. Shelton

About

Thomas Nichols was born in 1815 and raised in Orford, New Hampshire. At an early age, he became interested in self-betterment through healthy living. Although he was born 20 years after the founders of hygiene science, Thomas supported the hygiene movement’s beliefs. He also shared the zeal for doing good as other hygienists.

Thomas began to study medicine at Dartmouth at the age of 19. At that time, Sylvester Graham was lecturing in Boston on his Crusade for Health and Physiological Reform.

Thomas attended these lectures and immediately adopted Graham’s principles. Grahamites, as they were called, followed a vegetarian diet, had strict mealtimes, avoided spices and condiments, and abstained from tea, coffee, and alcohol. They also promoted breathing fresh air and bathing regularly.

Following Graham’s lectures, Nichols switched his studies from medicine to journalism. He spent the next few years traveling through the West and South, writing for various journals. Upon his return to New York, the position as editor of the New York Evening Herald was secured. He was deeply interested in health reform and had progressive views of women’s rights. He eventually met Mrs. Mary Gove as she began lecturing on Grahamism and women’s reform.

She devoted her life to educating women on health and wellness.

She devoted her life to educating women on health and wellness.

Mary also attended Graham’s lecture on the Crusade for Health and Physiological Reform in Lynn, Massachusetts. For her, converting to a Graham Lifestyle just made sense. Eventually, she connected with Thomas through her health lectures and advocacy in the women’s movement. Together, they supported this lifestyle and eventually were married. They diligently worked to promote health within the community.

At that time, there was strong opposition to women entering the medical profession. Mary was not allowed to attend medical schools or branches of medicine. Thomas realized that she was at a significant disadvantage. He then decided to complete his medical studies. He studied at the University of New York under Valentine Mott and graduated with high honors. He obtained his medical license and worked alongside his wife.

Ever the writer, Thomas wrote and edited the Water-Cure Journal and Herald of Reforms in 1845. Mary focused on writing the content, and it became their first significant project. These journals were devoted to physiology, hydropathy, and the Laws of Life. Through a series called Illustrations of Physiology, Thomas wrote about diet and health. Articles also addressed the water cure, hygiene, dietetics, and dress reform. Ten years later, the journal was renamed the Hygienic Teacher and Water-Cure Journal.

Realizing the need for education and training within the medical establishment, Thomas and Mary opened the American Hydropathic Institute in 1851. It was the first medical establishment created to teach the principles of water therapy. Dr. Nichols taught chemistry, anatomy, physiology, pathology, medicine, and surgery. Mary taught women’s physiology and the diseases of women and children. What is unique here is that men and women were equally accepted at the Institute.

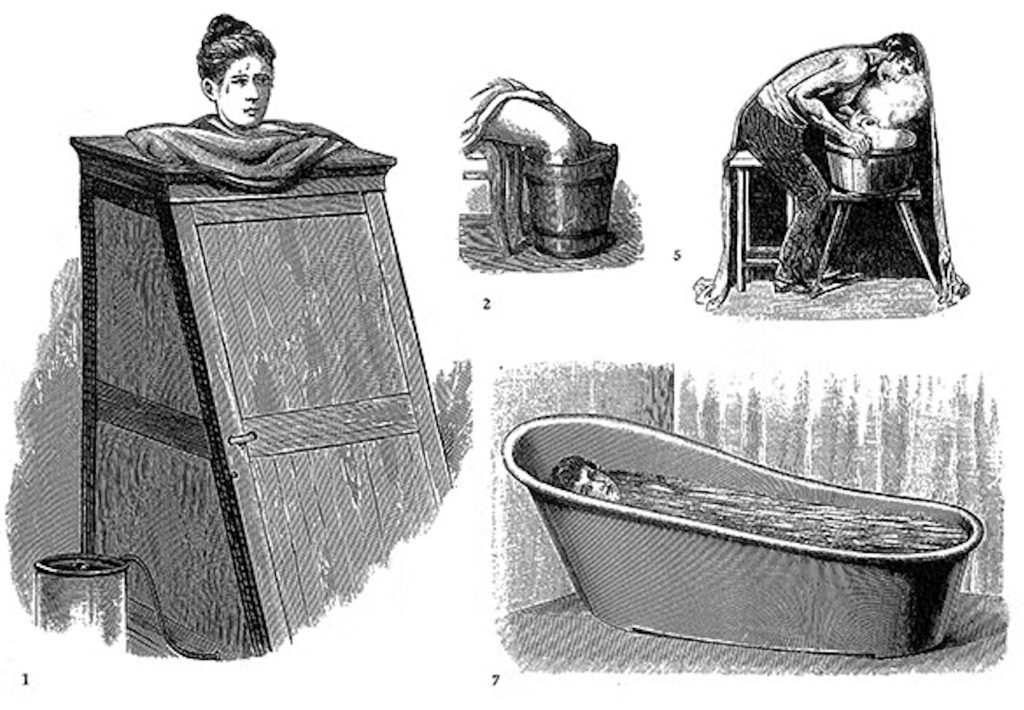

Hydropathy, which originated in the 1800s, believed that if water invaded cracks, wounds, or imperfections in the skin, it would flush out impure fluids. Hydropathic techniques included damp bandages, sweating, and a variety of baths (plunging, half bath, head bath, and sitting bath).

A large part of the lifestyle also focused on living simply. These lifestyle adjustments included dietary changes, fresh air, sleep, and drinking large quantities of water.

In 1853, they coauthored a new publication entitled Nichols’ Journal of Health, Water-Cure and Human Progress. It focused on individual and social health, education, hydrotherapy, women’s rights, and happiness.

Mary and Thomas next moved to Yellow Springs, Ohio, where they established another water cure institute in 1856. Their institute became both groundbreaking and scandalous at the time. Housing was provided for men and women. Studies included the health benefits of a vegetarian diet, the healing properties of hydropathy, and the importance of maintaining a disciplined life.

These positive attributes became clouded by Nichols’ belief in free love and the restraints of traditional marriage. Folks who felt strangled by the constructs of society were drawn to the institute and participated in free love practices. Thomas gave local lectures such as “Free Love: a Doctrine of Spiritualism.” These lectures were scandalous and deeply frowned upon by the local community. The public was not ready for this. Their advocacy of free love also alienated them from other reformers. Where they were once beloved reformers, these taboo ideas caused many followers to condemn these new beliefs. Their views were too abhorrent to merit a continued following.

When the Civil War erupted, Mary and Thomas boarded a ship and sailed for London. They detested war and would not support either side. Shortly after their arrival, they began writing for British journals. When the opportunity presented itself, they lectured on vegetarianism and the laws of health.

They moved to Malvern, England, and created another water cure treatment facility. Thomas wrote the Human Physiology, the Basis of Sanitary and Social Science. In his book, Dr. Nichols describes the causes of disease among hygienists. He notes that some in the profession regard disease as the diminution of the nervous power of what he calls the vital force (Isaac Jennings and Mary Gove Nichols). Opposing practitioners believed that the cause of all diseases involves impurities in the blood. (Russell Thacker Trall). Nichols himself, anticipating John H. Tilden by several years, adds: “But good blood cannot be formed without sufficient vital or nervous power, and good blood is necessary to the healthy action of the brain and nervous system. Here is reciprocal action, each depending upon the other. Waste matter, retained in the human system, becomes toxic and poisons the blood.”

By 1878, Thomas and Mary returned to editing and writing for the Herald of Health journal. Mary died in 1884, and Thomas continued with the Herald of Health until 1886 when he retired.

Thomas wanted to summarize his life’s work and what he learned. He also wanted to write a tribute to his beloved, who worked as a health educator throughout her life. He combined both in his book, Nichol’s Health Manual. He begins with a memorial to the life and work of Mary. He then discusses social conditions, marriage, human physiology, disease in general, female diseases, diet, digestion, and treatment. Hydropathy was explained, and various hydropathic processes were discussed. Included were also chapters on pregnancy, birth, and raising children. It is a profound testament to their life’s work.

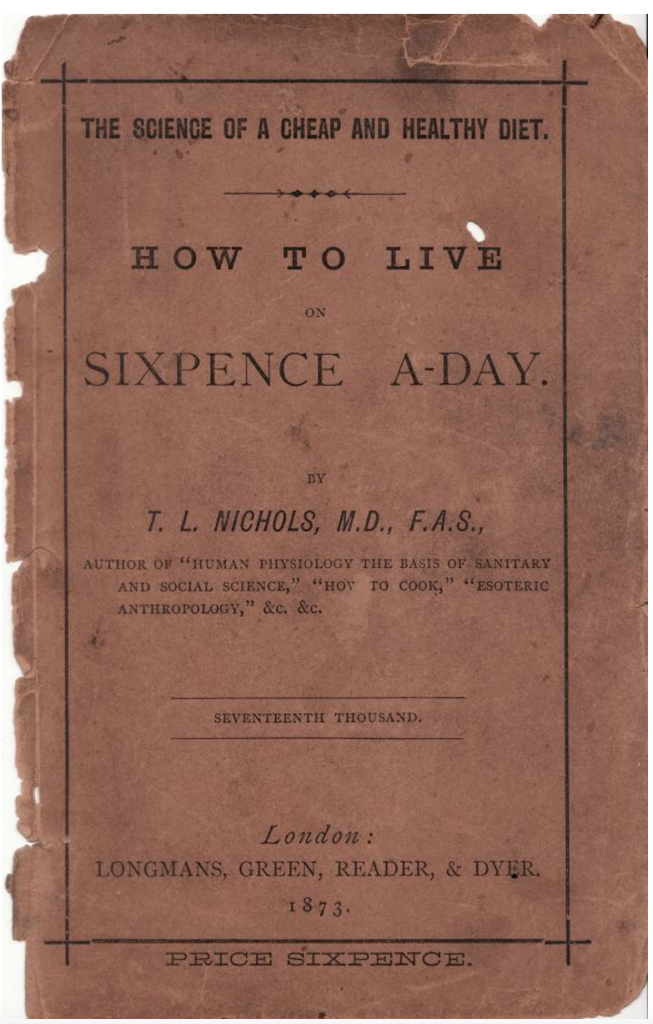

Thomas realized that people needed to learn how to become vegetarians. Practical information on this lifestyle was required in both England and America. He wrote How to Live on Sixpence A-Day and followed it up with How to Live on a Dime and a Half a Day. Thomas next wrote a more precise book on preparing vegetarian dishes and published How to Cook: The Theory in Practice with 500 Recipes.

Last but certainly not least, he wrote The Diet Cure. This informative work shares that humans are their healthiest when they follow nature and eat what was intended for them. That was his simple rule of health.

Life in the 1800s

The early 1800s was a time of outbreaks. Malaria and tuberculosis were the leading causes of death for adults, while children commonly died from measles, mumps, and whooping cough. The general death rate was high, and the illness recovery rate was low. Many mothers died in childbirth or from childbirth fever. People were not educated about nutrition, health, or their own body. The state of healthcare left much to be desired.

One of the most devastating events of the 1800s was the Civil War. Soldiers died from illness and infected wounds due to ignorance of germs and infection. Water was often contaminated, medical equipment was unsterilized, and doctors rarely washed their hands. Throughout the military camps, dysentery was the worst affliction, attacking the intestines through contaminated food or water.

Medicine during this period was a gruesome ordeal and seems incomprehensible today. Physicians frequently bled patients to “force” the disease “out,” and many died in the process. Blistering was also a widespread healing technique. For at least a century, strychnine, a potent poison, was the best remedy the profession had to offer for paralytic conditions. Quinine was frequently used for fever, with such side effects as severe bleeding, kidney damage, irregular heartbeat, and severe allergic reactions. Water was routinely withheld from the sick, heightening the chances of dying from dehydration. More often than not, the ‘cures’ were worse than the diseases!

Notable Achievements:

As well as becoming a medical doctor, Thomas was a prolific writer, honing his skills as a journalist and editor. In 1845, he began the Water-Cure Journal and Herald of Reforms, which was devoted to physiology, hydropathy, and the laws of life. The journal also included articles about individual and social health, education, hydrotherapy, women’s rights, the water cure, hygiene, dietetics, and dress reform. Thomas edited the journal, and he and Mary wrote it together. It was their first significant project. The journal continued with the new name, Hygienic Teacher and Water-Cure Journal.

Thomas and Mary realized they must train future doctors on their principles. In 1851, they opened the American Hydropathic Institute. It was the first medical establishment created to teach the principles of water therapy. It was also revolutionary as it was equally open to men AND women. It was one of the first institutions to offer women a medical degree.

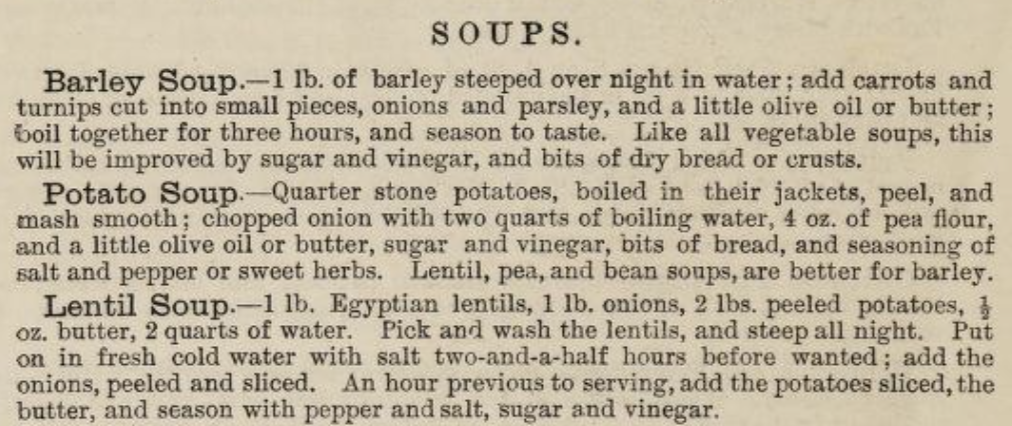

Thomas realized that people needed to learn how to live a vegetarian lifestyle in England and America. He wrote How to Live on Sixpence A-day and followed it up with How to Live on a Dime and a Half a-Day. The book lists some of the more famous vegetarians of the time. He explains why you should become a vegetarian and the nutritional value of grains, fruits, vegetables, and legumes. He discussed when, what, how often, how much to eat, and what to drink. He also suggested learning to prepare a dozen recipes and teaches you how to prepare bread, porridge, soups, potatoes, salads, sauces, pies, and other simple dishes.

Thomas followed these publications with a more precise book on how to cook vegetarian dishes and published How to Cook: The Theory in Practice with 500 Recipes. He explains the general principles of cooking, food, and its relationship to health. He shares recipes for sauces, vegetables, soups, fruits, salads, etc.

Dr. Nichols lectured extensively in this country and England. He left no stone unturned to help those who needed the gospel of hygiene.

Over the next decade, Thomas continued to write. He wrote the Human Physiology, the Basis of Sanitary and Social Science. In this book, Dr. Nichols defines his views on the cause of disease among Hygienists.

After his beloved wife Mary died, Thomas summarized what he had learned throughout his life and published Nichol’s Health Manual. He intended it to be a handbook of health and a tribute to the woman he married and her life’s work, especially for women’s health. He begins with a memorial to Mary and then discusses social conditions, marriage, human physiology, disease in general (especially female diseases), diet, digestion, and treatment. Hydropathy was explained, and various hydropathic processes were discussed. Included were also chapters on pregnancy, birth, and raising children.

Last but certainly not least, he wrote The Diet Cure, sharing in this book that humans are best when they follow nature. That is the simple rule of health. Every creature on Earth has its own natural food. Man naturally eats, lives, and thrives upon fruit, vegetables, seeds, and simple foods. Man is at his best when he eats the food best adapted for nourishment. When he departs from that, his body becomes disordered and diseased. He discusses quantity, quality, when, and what to eat and drink. He explains the importance of water for health, the water cure for treatment, fresh air, and exercise.

Learn more from: (Read direct excerpts)

- Shelton, Herbert. (1934). The Science and Fine Art of Natural Hygiene – The Hygienic System: Volume I. National Health Association, Youngstown, OH.

- Shelton, Herbert. (1934). The Science and Fine Art of Fasting. Hygienic System – Volume III. National Health Association, Youngstown, OH.

- Shelton, Herbert. (1968). Natural Hygiene: The Pristine Way of Life Youngstown, OH. National Health Association.

- Shelton, Herbert. (1968). Fasting: For the Renewal of Life. Youngstown, OH. National Health Association.

- Graham, S., Trall. R., Shelton, H. (1972). The Greatest Health Discovery. Youngstown, OH. National Health Association.

- Lennon, J., Taylor, S. (1996). The Natural Hygiene Handbook. National Health Association, Youngstown, OH.

The NHA wishes to remind the readers that nothing in this or other publications is intended to constitute medical treatment or advice. Readers should further be aware that in several areas, previous publications do not reflect the NHA’s current teachings or health approaches.

Our Mission

The mission of the National Health Association is to educate and empower individuals to understand that health results from healthy living. We recognize the integration of all aspects of health: personal, environmental, and social.

We communicate the benefits of a plant-based diet, exercise and rest, a healthy environment, psychological well-being, and fasting when indicated.

SUBSCRIBE TODAY AND NEVER MISS AN UPDATE

SUBSCRIBE TODAY AND NEVER MISS AN UPDATE