(1830 – 1911)

About

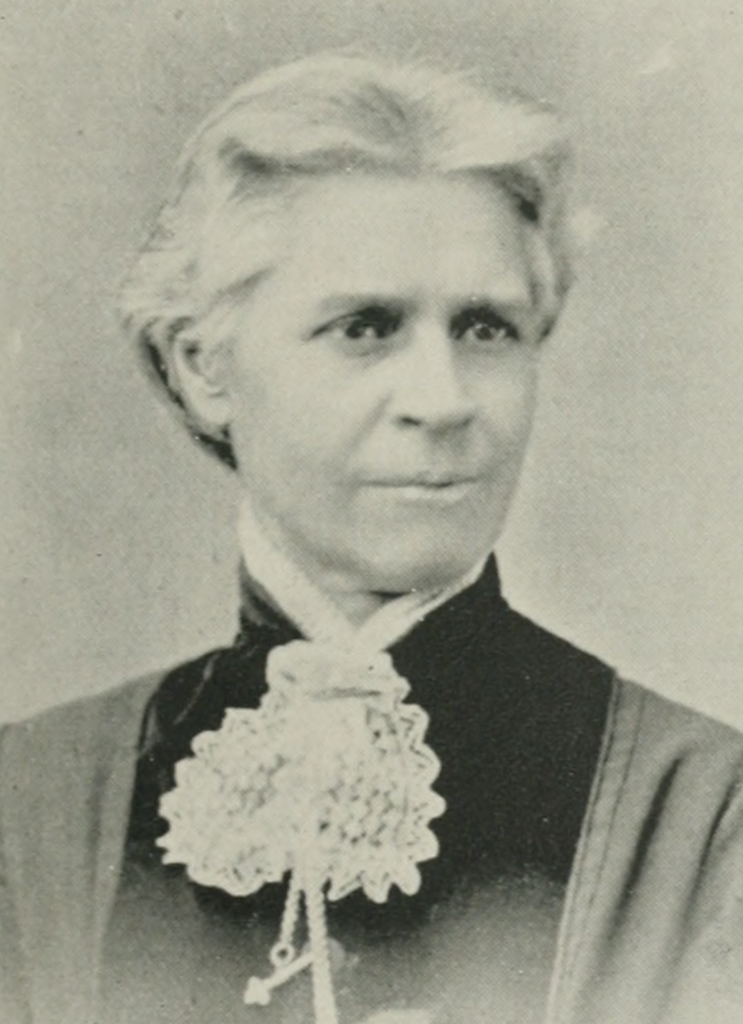

Susanna Way Dodds was the firstborn of Anthony and Rhoda Way on November 10, 1830, in Randolph County, Indiana. Here, she received a common-school education. Susanna, the eldest of a large family, was ambitious and, at an early age, set her heart on becoming a doctor. To her great disappointment, she found that no college would admit women.

At this point, there were only ladies’ seminaries. She, therefore, decided to go to the Oxford Female Institute, which Rev. J. W. Scott, the father-in-law of President Benjamin Harrison, then conducted. To be financially able to do this, Susanna began teaching at seventeen in elementary schools with a salary of eight dollars a month. By rigid economy, she could pay her tuition, and at twenty-three, she received her diploma from Dr. Scott’s seminary. Her much-coveted medical degree was still in her plans.

The University of Ann Arbor was founded, and its doors were soon opened to women. In the spring of 1856, Susanna entered the preparatory department of that college. However, due to a family illness, she had to postpone her plans and returned home.

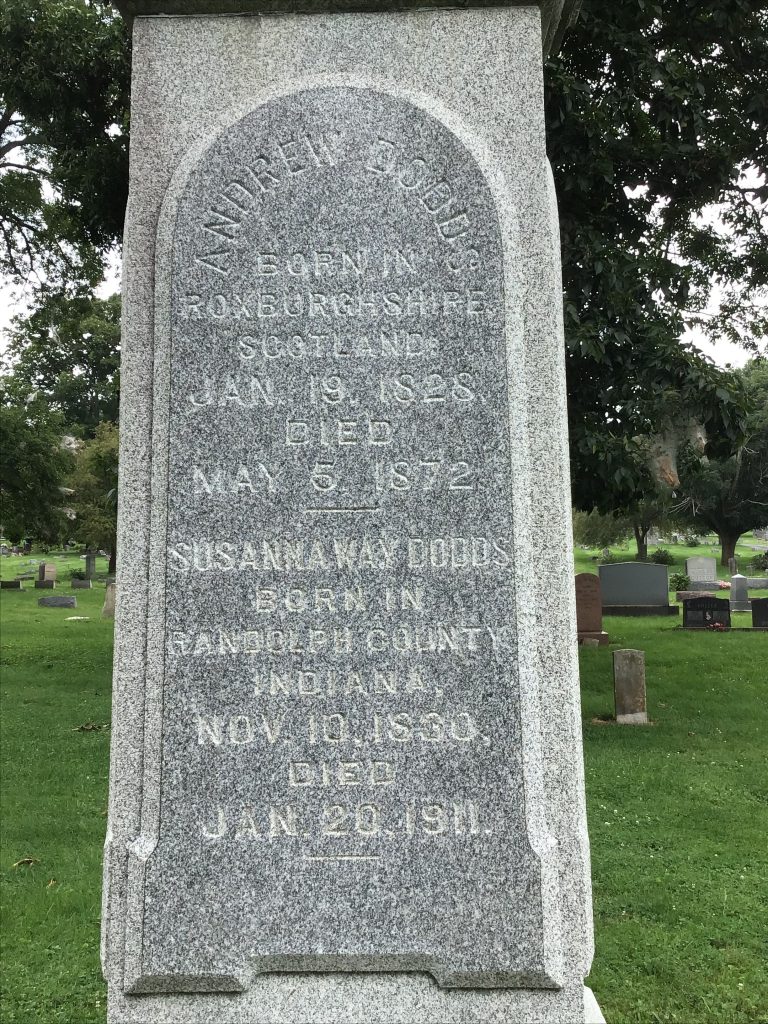

The following year, she married Andrew Dodds on November 10th, 1857. His liberal views were in harmony with her own. They made their home in Yellow Springs, Ohio, and the now-Mrs. Dodds renewed her studies at Antioch, where she graduated.

She also enrolled in and graduated from Russell Thacker Trall‘s New York Hygeio-Therapeutic College, becoming the fourth woman in the country to become a physician. Susanna supported the hygienic method of disease treatment.

During the Civil War, her husband enlisted in the Federal army. During a campaign in Virginia, he contracted an unknown disease and became extremely ill. Before his death, the family moved to St. Louis, Mo. Her husband never regained his health, and he died on May 5th, 1872, at the age of 44. He was buried in Yellow Springs, Ohio, where they began their married life.

Dr. Dodds started practicing medicine in 1876 in St. Louis with her husband’s sister, Dr. Mary Dodds, with whom she remained associated until her death.

In 1878, Dodds and her sister-in-law opened the Dodds’ Hygeian Home facility. In their practice, they used only hygienic or natural treatment methods, such as diet, exercise, massage, and hydrotherapy, and had phenomenal success in curing both acute and chronic patients. Except in cases involving pain relief, such as in the last stages of cancer or other incurable diseases, no drugs were ever used. Women’s diseases and digestive disorders were their specialties; however, they also treated other chronic illnesses.

In 1887, the Friends of Hygiene called a meeting in St. Louis to consider founding a hygiene college. The result was the establishment of the St. Louis Hygienic College of Physicians, incorporated by the State of Missouri on August 5, 1887. Dr. Susanna Dodds was both the College Dean and a faculty member. Unfortunately, after operating for a few years, it was discontinued due to a lack of funds.

Throughout her life, Dr. Susanna was a prolific writer and contributed to several health journals and other papers. Her first published work was “Health in the Household, or Hygienic Cookery,” which covered the many aspects of the hygienic diet. The next book, “Race Culture,” was a comprehensive and practical book for women. It taught women the secret of health and happiness and shared how enlightened motherhood would improve the human race.

Dr. Dodds was very strenuous in advocating the principles laid down by Russell Thacker Trall, Sylvester Graham, and other pioneers in hydropathy and hygienic living. She wrote, “We need books, journals, papers, hygienic restaurants, and many other influences to spread these doctrines.”

For 50 years, Dr. Dodds was head of the Dodds Hygienic Facility in St. Louis, Missouri, and one of the country’s eminent hygienists. She was Vice President of the Vegetarian Society of America and published The Sanitarian magazine.

Susanna died on January 20th, 1911, at the age of 80, and was buried in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Through her work, she greatly influenced the Natural Hygienist Herbert M. Shelton, one of the founders of the American Natural Hygiene Society (ANHS) in 1948. This eventually evolved into the National Health Association as we know it today in 1999.

Over their lives, Susanna and Mary Dodds, as physicians, positively impacted women’s physical health and development on many levels.

Life in the 1800s

The medical “art” in America during this period seems incomprehensible today.

Quote

If you got sick in the early 1800s, you were a candidate for other such barbaric “care” as bleeding, applying leeches directly on your skin, blistering, burning, and cauterizing (to “draw” the pain away); forced purging and vomiting; and, of course, taking highly-toxic (and long since abandoned) drugs. Water was routinely withheld from the sick, heightening your chances of dying from dehydration. The death rate was relatively high, and the illness recovery rate was extremely low. The ‘cures’ were often worse than the diseases.

(Excerpt from the Natural Hygiene Handbook)

The 1800s witnessed the evolution of various schools for healing; folk medicine became almost obsolete. Considerable medical literature with Latin and Greek terminology had accumulated, and medical colleges (schools of medicine) had been established.

However, the Civil War, 1861- 65, and the decades following it had a devastating impact and stress on the country. Due to a lack of funds, hygienic colleges, magazines, and institutions closed, and the hygiene movement never regained its dominant position.

The Civil War setback, the panic of the 1870s, Dr. Russell Thacker Trall’s college closing, and his death caused the movement to be at a standstill. Dr. Susanna W. Dodds stepped up and established the St. Louis Hygienic College of Physicians and Surgeons. However, it was short-lived due to a lack of funds.

the St. Louis Hygienic College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Hygiene and health became very popular in the 1800s among healing practitioners and the public. However, in the 1900s, the movement lost ground to the medical (allopathic, drugging) system, which had a powerful ally in the Rockefeller drug and oil empire. The medical system gradually adopted the sanitation part of Hygiene while rejecting its “no-drugs” philosophy.

In the early nineteenth century, women had no access to higher education or other professions, and married women had no legal identities apart from their husbands. Society dictated that the woman’s place was in the home. This Victorian ideal never coincided with reality. As soon as it evolved, radical feminists challenged it, seeking to expand or redefine a woman’s proper sphere. The late 1840s saw the onset of several waves of feminist activity and social reform, with women earning their medical degrees. It is part of the nineteenth-century reform movements, especially health reform, which encompassed not only public health and social hygiene but the transformation of medicine itself.

Women were found to be the strongest champions of “woman’s rights” among the Hygienists. Indeed, Hygienists played a leading role in the reform movement of the time and left a profound mark. If a complete history of the nineteenth century is ever written, hygienists would play a prominent role.

Aspiring woman physicians, nevertheless, faced monumental difficulties. Throughout the nineteenth century, the debate raged on the propriety of women practicing medicine. In 1871, American Medical Association President Alfred Stille held that women were morally unfit to practice medicine. The modesty argument was also used against women in medicine. The fact that women could enter the medical profession during the nineteenth century was mainly due to its chaotic state. Not surprisingly, the medical profession was in a state of flux. Due to the war, it lacked cohesion and the ability to regulate itself.

Women were attracted to unorthodox branches of medicine in proportionally higher numbers than men. Homeopathic practices were especially attractive to women reformers and physicians. St. Louis Children’s Hospital was staffed exclusively by homeopathic physicians until 1910. Homeopathic medical colleges were more willing to admit women into their ranks than were allopathic traditional medical institutions.

Women physicians arrived in St. Louis in the late 1860s. Over the next fifty-plus years, the number increased as more arrived and St. Louis medical colleges began admitting women. Trained female midwives and colleges of midwifery also appeared in St. Louis. In 1860, the St. Louis City Directory listed only one midwife; by 1900, the number exceeded 300.

Life in the 1900s

By 1900, however, approximately 7,000 women had entered the medical profession. Women at several coeducational medical colleges comprised at least ten percent of the enrollment. By 1920, women had established their undisputed right to study and practice medicine. However, their numbers declined over the next few decades and then began to rise again in the 1960s.

Impact of Diet and Lifestyle

In the early 1800s, some medical doctors discovered that discontinuing drugs and surgery gave better results to their patients. New methods like fasting and raw diets were developed. Exercise, sunshine, and fresh air were recommended, and a comprehensive “medical” theory about natural healing and health was created. In Europe, this new science was called “Nature Cure,” and in the USA, “Hygiene” or “Orthopathy.” Between 1820 and 1850, movements in Europe and the USA compromised a significant reform (like anti-slavery, women’s rights, etc).

Hydropathy spread quickly, with over two hundred cure centers established between 1843 and 1900. Although most treated both sexes, the centers were especially popular with women. Women who were denied access to the “regular” medical field gained acceptance and took the lead as water-cure physicians. The introduction of hydropathy into this country occurred twenty-two years after Dr. Isaac Jennings had discarded the drugging system and adopted the Hygienic practice. The Hygienic movement had already been established, with thousands of followers, when the water cure was introduced.

Many physicians who utilized the water cure thought of it as a treatment that could replace drugs altogether. In other words, they professed to be able to do with water everything that they had formerly sought to do with drugs. Its books and magazines already had a wide circulation. Significant numbers of physicians had lost confidence in drugs and took advantage of the water cure as a means of escaping the drugging system. Even though they adopted more or less Hygiene in connection with their water-cure practices, they called their practice hydropathy.

Impact of Clothing

Women wore dresses with large, voluminous skirts. Layers of petticoats were used to create these large skirts, which were then replaced with the crinoline. The crinoline was an undergarment of steel hoops, forming a cage for skirts to lay over them.

In the 1850s, it was common for women to wear two-piece dresses (a separate bodice and skirt). The weight of the skirts made it challenging to move quickly, and the corsets made breathing difficult. The skirts were extremely cumbersome and challenging in many ways. Working alongside an open hearth became a significant health hazard, as long skirts easily caught fire.

Corsets tightened the waist, squeezed the chest, and made breathing shallow. By the 1830s, steel replaced whalebone, making the corset significantly tighter. This action forced the ribs closer together and narrowed the entire rib cage. Internal organs shifted to accommodate the new shape. The heart was pushed into the chest cavity, and the intestines were forced downward. Rib compression prevented the lungs from fully expanding, resulting in shortness of breath, fatigue, and, at times, a loss of consciousness. For this reason, carrying smelling salts was a necessity for women.

Corsets also negatively impacted the organs below the ribcage, deformed the ribs into an “S” shape, and misaligned the vertebral spines.

For these many reasons, Dr. Dodds discarded the regular female attire and wore pants. That was daring in those days, but it took daring to be a Hygienist.

Hygienists espoused many causes, such as vegetarianism, temperance, clothing reform, sex education of the young, and teaching physiology and Hygiene in public schools. However, Susannah Dodds, M.D., and other women hygienists also strongly supported women’s rights and the dress reform movement.

Teachings

QUOTE

The mother who sets spiced and highly seasoned food before her children has little idea what she is doing. No mother’s son ever fell victim to drink or even to the tobacco habit until the way had been well paved by stimulants in food. All actual reforms ought to begin in our homes where the children are reared. The young man whose body has been fed with wholesome, nourishing food that is free from stimulants will not easily fall prey to tobacco or alcohol.

—Dr. Susanna Way Dodds

The early hygienists knew of the advantages and superiority of hygienic care over drug treatment during the convalescent period. Dr. Susanna Dodds learned from Dr. Russell Thacker Trall not to overtax patients. He insisted that “no extra demand upon the patient” be made during the post-critical stage. She adds that he applied the same rule to all people, whether well or ill, reminding his students to work with the patient’s vitality. To waste a patient’s vitality would diminish his chance of recovery. No part of a patient’s recovery was ever to be taxed.

Conservation of a patient’s energy and resources was the secret of the success of Dr. Isaac Jennings, Robert Walter, and Dr. John Tilden. They had been outstandingly successful in their care of the sick. None of these men sought to cure the disease; instead, each recognized that overfeeding, over-bathing, over-sunning, over-exercising, and aggravating patients in any way overtaxed them and retarded their recovery.

The advantages and superiority of hygienic care over drug treatment are shown through a patient’s rapid healing and recovery speed. Proper care of the sick through Hygienic methodology involves “no drug interventions” and no measures of force. Any attempt to hasten convalescence by force will only delay full recovery.

Mary Gove-Nichols, Dr. Harriet Austin, and Susanna Dodds were at the forefront of sex education for women and children, human rights, women’s rights, and clothing reform for women. The clothes worn by women of that period were horrific. Stiff whalebone corsets and long dresses inhibited breathing and greatly restricted movement. Even before the Civil War, Austin and Dodds advocated for and wore slacks as a matter of health and equality.

The practices of the early Hygienists were a composite mixture of hygiene and hydropathy, while most of the practitioners were designated as hydropathists. We must keep these distinctions in mind. Physiological reform (Hygiene) originated in this country, while hydropathy originated in Europe. The two movements mingled and paralleled each other for a time, but they were separate and distinct in the clear evolution of the Hygienic System.

Other evidence of the emphasis on hygiene and the trek away from hydropathy is found in the titles and the subject matter of other Hygienic magazines of the time. Dr. James Jackson called his magazine The Laws of Life. Mrs. Ellen G. White, leader of the Seventh Day Adventists, embraced hygiene, propagated it among her religious followers, and entitled her magazine Health Reform. Dr. Robert Walter named his magazine The Laws of Health, and Dr. Susanna Dodds published a magazine under the title of The Sanitarian.

Many thought Dr. Russell Thacker Trall was a hydropath; his written work The Encyclopedia proves it. However, his philosophy and practice underwent considerable evolution towards the hygienist movement over the rest of his life. Such an argument would cause one to say that Martin Luther was a Catholic priest, for he certainly was before he became the leader of the German Reformation movement. Just as Luther became a protestant, so Trall became a Hygienist.

Notable Achievements

Dr. Susanna Dodds was the fourth woman in the country to become a physician, graduating from the Hygeo-Therapeutic College of New York, operated by Dr. Russell Thacker Trall. Susanna’s hygienic practice and gender kept her outside the St. Louis medical establishment. Thus, she did what many female social reformers and physicians had to do and founded her own institution.

graduating from the Hygeo-Therapeutic College of New York

Joined by her sister-in-law, Mary Dodds, a hygienic physician, they opened their facility, the Dodds’ Hygenic Home, in 1878. In their practice, they used only hygienic or natural methods of treatment: diet, exercise, massage, and hydrotherapy. They had phenomenal success in curing both acute and chronic patients. Except in cases for relieving extreme pain, as in the last stages of cancer or other incurable diseases, drugs were never used. Though diseases of women and digestive disorders were their specialties, they also treated other chronic illnesses.

Dr. Russell Thacker Trall’s death left the movement practically leaderless. With his college closed, Trall gone, and no one ready and willing to take the helm, the movement lagged. There were men who could have led, but they seemed reluctant to do so. Indeed, disagreements broke out among them, which tended to paralyze further action.

Dr. Dodds tried to resurrect the movement with her sister-in-law, Mary Dodds, and they founded the St. Louis Hygienic College of Physicians and Surgeons. They focused on natural methods of treatment: diet, exercise, massage, and hydrotherapy. On its staff were Dr. Susanna Dodds, as hygieotherapist and Dean; Dr. Luteys, a homeopath, who taught chemistry; Dr. Stickney, an allopathist, who taught the anatomy of surgery and two other physicians of the regular or allopathic school. Besides being taught hydro-hygienic theories and practices, the students were taught enough allopathic theories to pass the state boards. A strict hygienic vegetarian diet was taught, which also forbids the consumption of baking powder, meat, milk, soda, spices, and sweeteners. They did not use any drugs except in cases for relieving pain.

Under the leadership of Dr. Susanna Dodds, The St. Louis Hygenic College of Physicians and Surgeons graduated several classes before closing due to lack of funds. After its closing, Dr. Robert Walter also tried to establish a college. The effort failed. Had either college succeeded, the hygienic movement would have been revived. Unfortunately, theirs was the only attempt to establish a college of Hygiene after Dr. Russell Thacker Trall’s death.

Dr. Susanna was a prolific author and contributed to several health journals and other papers. She also published a magazine under the name The Sanitarian. Her first published work was The Diet Question. In this book, Dr. Dodds covers the many aspects of the hygienic diet. In part one, she discusses the reasons why: Health in the household, Food, and Physical Development, with a deep dive into the food groups (fruits, vegetables, bread, meats, milk, butter, eggs, salt, sugar, tea, coffee, alcohol, condiments, and abstaining from drinking at meals, etc.), dietician rules, and cooking tips. Health in the Household, or Hygienic Cookery, covered the many aspects of the hygienic diet and included quite a few recipes. Her next book, Race Culture, was a comprehensive and practical book for women. It taught women the secret of health and happiness and shared how enlightened motherhood would improve the human race.

Dr. Dodds lived into the twentieth century and continued to shock the prudish of her era by wearing pants instead of dresses.

Perhaps the most outstanding woman graduate of the Hygeo-Therapeutic College was Susannah Way Dodds, M.D., whose writings and lectures on Hygiene constitute a valuable addition to Hygienic literature. Susanna and Mary Dodds, as physicians, have done much for women’s physical health. Through her work, she greatly influenced the Natural Hygienist Herbert M. Shelton, who became one of the founding members of The American Natural Hygiene Society (ANHS) in 1948. In 1999, it evolved into the National Health Association (as we know it today).

- Graham, S., Trall. R., Shelton, H. (2009). The Greatest Health Discovery. Youngstown, OH. National Health Association.

- Lennon, J., Taylor, S. (1996). The Natural Hygiene Handbook. National Health Association, Youngstown, OH.

- Shelton, Herbert. (1974). Fasting For Renewal of Life. Youngstown. National Health Association

- Shelton, Herbert. (1934). The Science and Fine Art Fasting – The Hygienic System: Volume III National Health Association, Youngstown, OH.

- Shelton, Herbert. (1934). The Science and Fine Art of Natural Hygiene – The Hygienic System: Volume I. National Health Association, Youngstown, OH.

- Shelton, Herbert. (1968). Natural Hygiene: The Pristine Way of Life. Youngstown, OH. National Health Association.

The NHA wishes to remind the readers that nothing in this or other publications is intended to constitute medical treatment or advice. Readers should further be aware that in several areas, previous publications do not reflect the NHA’s current teachings or health approaches.

Our Mission

The mission of the National Health Association is to educate and empower individuals to understand that health results from healthy living. We recognize the integration of all aspects of health: personal, environmental, and social.

We communicate the benefits of a plant-based diet, exercise and rest, a healthy environment, psychological well-being, and fasting when indicated.

SUBSCRIBE TODAY AND NEVER MISS AN UPDATE

SUBSCRIBE TODAY AND NEVER MISS AN UPDATE